The Possibility of Nature

by Stefano Castelli

The concept of nature has for some time now - and by force of

circumstances - come to be both indirect and mediated. Not only as

the result of the difficulty of coming to terms with "authentic" nature

due to a process of urbanisation which is by now more than

consolidated but also because the concept has come to form part of

that category of commonplaces of 'postcard images', either of false

exotic travels or else as a photo feature. And this process naturally

forms part of the general decline in values suffered by the concept of

reality which is increasingly more difficult to grasp and distinguish

from simulation as the result of the virtualisation and digitalising of

the world.

And so also in the artistic field the idea of nature has suffered an

analogous destiny. Both because the "reasons" in their own right - the

classical subjects - are no longer actual and also because the artist's

commitment-cum-involvement is addressed to the condemnation of

the expropriation of nature rather than to its mere description.

Without choosing univocal solutions or extreme forms of

deconstruction, reexamining "traditional" means without recourse to

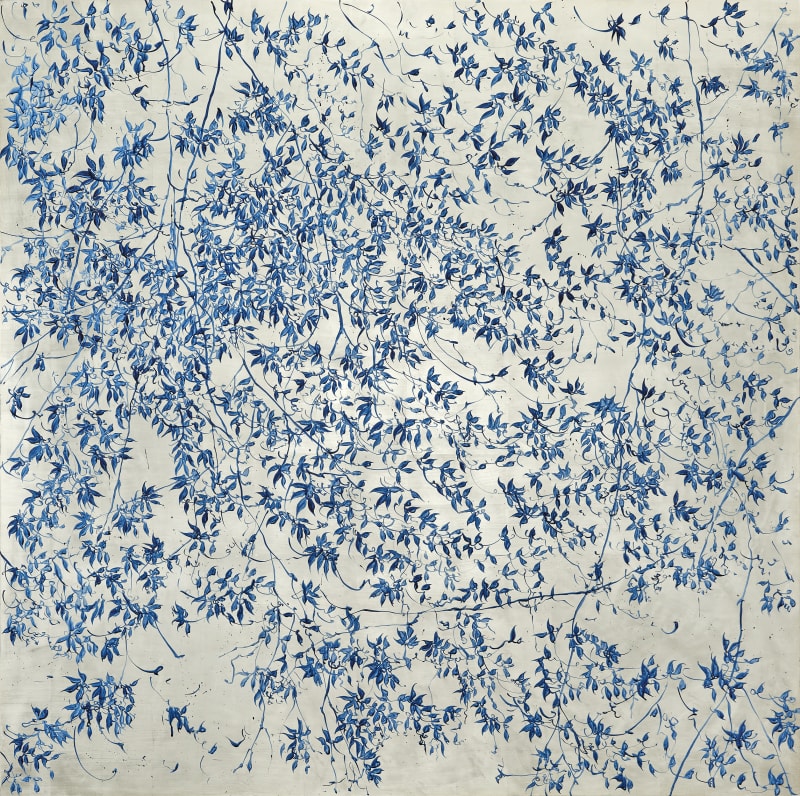

any habitual form of realism, Sue Arrowsmith and Matteo Montani

both concern themselves with the idea of nature. The interior dynamics

of their works follow different paths which only partially come

together in the meeting point of this exhibition. Sue Arrowsmith uses

nature as an iconographic cue to then analyse, question and "open" it

in a context that goes beyond the initial reference. Matteo Montani,

instead, "undoes" the figurative reference in such a way that the work

is able to be approached from different starting points. In his case, in

fact, one can think of a figure that is intensified almost to the extent of

abstraction, or elseidentify in his work forms that are not referential and that 'coagulate'

to the point of suggesting the random or chance idea of a figure.

Both artists gracefully destabilise the viewer, inside plainly apparent

traits hiding others. Above all in the new works which use sheet metal,

for the English artist the concepts of grace, harmony and preciosity are

the condition and way for a vision that embodies parts of what is

unclear, not decorative, not realistic and not merely of a

"photographic" nature. As regards the Roman artist, his "pictorial

effects" are hooks on which the vision can hold on to which lead,

however, to something else: filterings, gestuality and dilution really

don't conquer the scene but instead make way for an image sui generis

which, moreover, is not an "image" in the complete sense of the term.

In the works by Sue Arrowsmith the figure is not presented as such.

In part it hides itself, as if "backlit", like a phantasmic presence. The

works seen from close-up render what is not visible as important as

what is shown. The figure remains suspended between idealism and

concreteness. Everything considered, what is not directly visible

underlines the role as protagonist taken on by the human eye, of that

of the viewer of the work. The variation - and therefore the repetition

- of the natural motifs furnish another fixed point which permits the

creation of peculiar atmospheres: what is generated is a sort of

algorithm that nevertheless leaves considerable room for the random

dimension.

In her own words: "All the paintings of this exhibition were obtained

from the same tree, photographed again and again in different periods

of the year. The images were then projected on a prepared surface. I

simply use nature and plants as a pictorial cue. In this way I can let the

marks generated by my brushstroke express themselves, and so

experimenting the 'reassurance' given by the forms and by the

resemblance between them. Sheet metal has become an important

element: the painting shines on the surface, brilliant and earthy. I'm

fascinated by the light and space given by the contrast of forms in

positive and negative. My work is never immobile. It's characterised

by movements midway between the visible and the invisible, between

sharpness and being out of focus".In the works by Matteo Montani the painting is instead liquid,

undulatory and "seismographic". Everything is played out in the space

between fullness and instability in a paradoxical static movement. The

possibility that here we have to do with landscapes is a sensation which

is at one and the same time concrete and impossible to remove, but

also never completely overt. The composition is studied in its details

although it presents itself to the eye as if still being defined.

Irrespective of the apparent randomness, also here there 'reigns' the

idea of a sort of matrix, of an underlying system which can reproduce

and regenerate itself, giving life to new forms (hypothetically inside

the same painting or concretely in the successive ones). The work is at

the same time a concluded conformation and the trace of something

that remains concealed to which one doesn't have access but the

presence of which makes itself felt like an afterthought. In short, what

is investigated is the "possibility of a figure".

As Montani explains: "During recent years my work has

progressively moved towards a vision that can more strictly be

associated with the landscape. The "procedural" aspect of my painting

has become accentuated. The vision reaches out to an eye on the world

and not on painting in itself. I'm interested that new signs and new

pictorial solutions can lead the eye to coincide with an interiorised

image of the world while, at the same time, 'looking out' on the world.

In the landscape in these most recent works we have the fusion of the

material and the immaterial dimension of the image, recomposing the

rupture that separates them".

Earlier in this text I touched on the question of the unattainability of

reality, of its disappearance in a tangle of the concrete and the virtual.

If the works by the two artists do not directly deal with digital

aesthetics one can nevertheless extract from them a comment

regarding the randomness of the image and of representation (the

difficult distinction between figure and abstraction, and their mixing

in the works by both artists is a symptom of this). In fact, it's as if the

images proposed by them were "transmitted" from a distance to the

viewer. In consequence, both artists investigate the moment in which

the manifestation of the figure is still a potentiality.

Obviously enough pictorial language cannot forget the context

(cultural, ideological and technological). By way of the question ofoptics in Montani and of the eye in Arrowsmith, the human being is

indirectly called into play. Mankind's absence, however, poses

questions. Is there still a relationship of interdependence between

mankind and its environment? Is the independence of nature still

actual; does it still carry out its cycle and is real, it realises itself

notwithstanding whatever kind of mediation? And, in abstracting

ourselves from the present and looking at "eternal" questions, is it

really possible to distinguish between nature and culture, does the

object of vision exist independently with regards to the human eye?

The works by these two artists are - everything considered - the

representations of "middle grounds", not vague but alternatives to the

consolidated definitions and to the functionality of a certain and

definitive cataloguing of things.